Book Review: Guide to the Terrestrial Mammals of Southern California and the Eastern and Southern Sierra Nevada, by Brad Blood

Brad R. Blood’s new Guide to the Terrestrial Mammals of Southern California and the Eastern and Southern Sierra Nevada just arrived and it is an excellent resource for those wanting to find any of the 150 mammal species that occur across this sizeable and very diverse chunk of California.

Brad, consultant, and also a research assistant at the LA County Museum of Natural History, is one of California’s most eminent mammalogists. He has been following mammalwatching.com for a while and members of our community helped source photos for this new book.

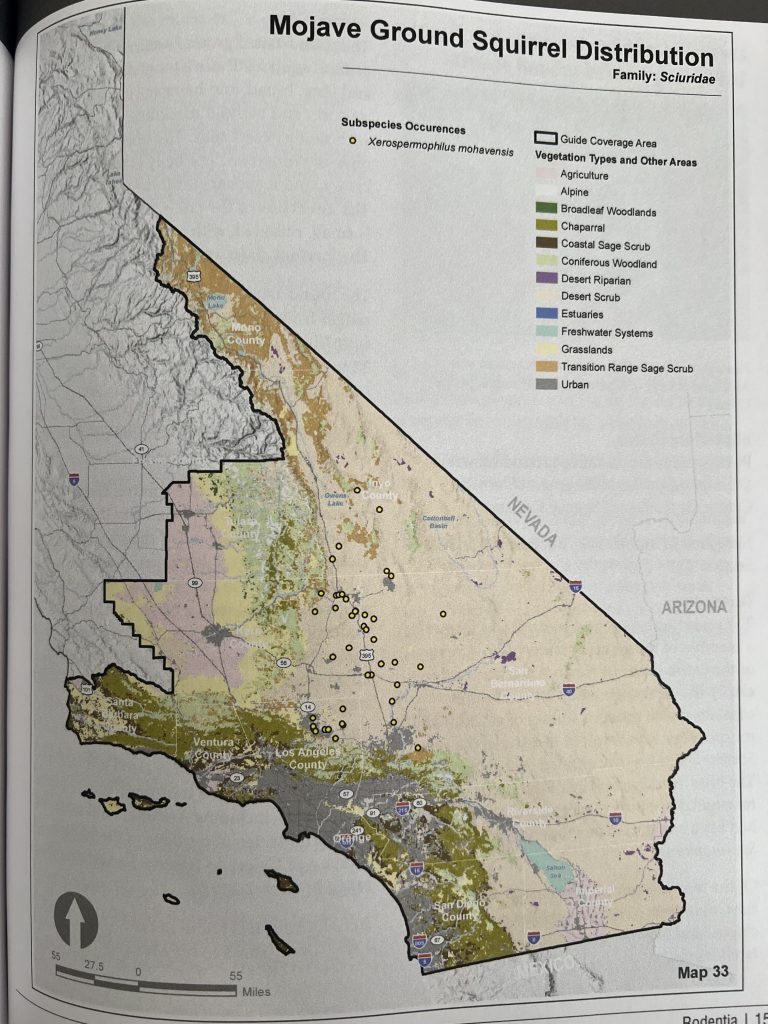

This is a comprehensive book – more of an encyclopedia really. And I had not appreciated how comprehensive it was going to be until it arrived! It has two or more pages of information for each species including one or more photos plus a detailed range map, based on museum records, that ought to be particularly useful.

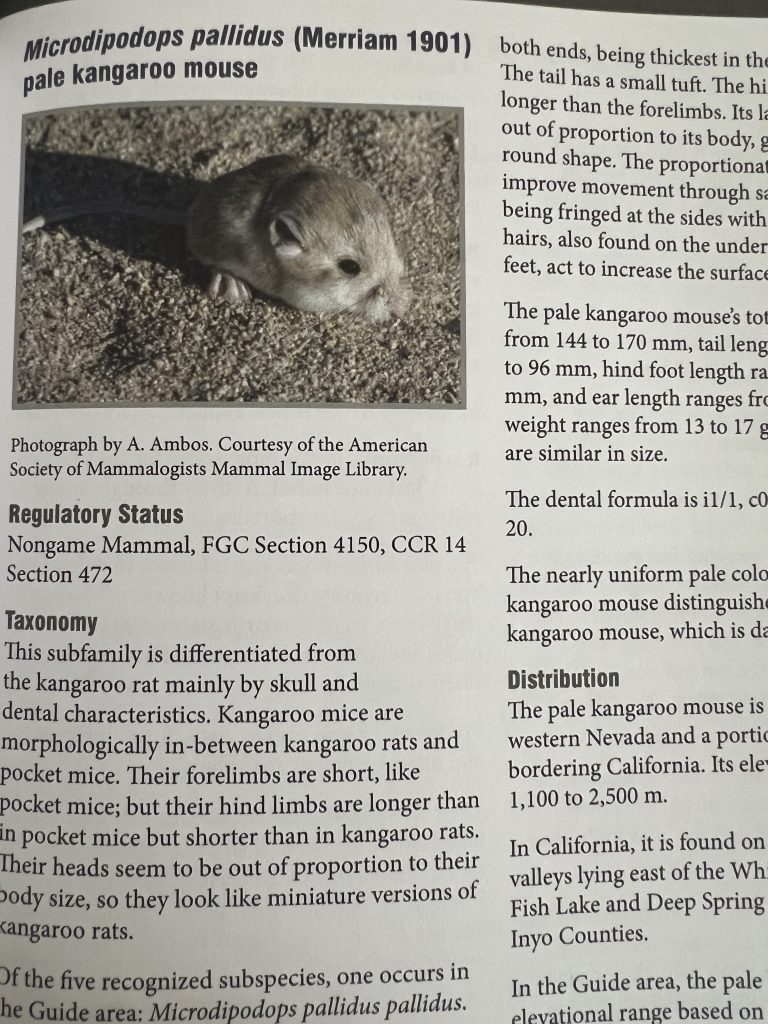

There is also information on taxonomy, including subspecies, and descriptions of each species and their ecology with some great trivia. Did you know for instance that the Pale Kangaroo Mouse is reported to “sleep on its back with its forelimbs stretch over the head and its hind limbs over its belly”. Adorable.

A great gift for any mammal nerd who is planning to visit California.

The book is published by Outskirts Press and – in the USA at least – seems widely available from Amazon, Barnes & Noble and elsewhere.

Jon

Post author

1 Comment

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

charleswhood

Thank you Jon for alerting us about this book, which I did not know was coming. As the sample range map shot shows for Mojave ground squirrel, if you’re planning a rodent-centered California trip, this book really does need to be part of your life. From the text with that entry I learned that these squirrels are most active early in the morning; I think when I’ve gone out with others, we’ve gotten too late of a start. The problem here is that the maps can be hard to read and there are no dates, so for example for southerly porcupine records, I would love to know when those specimens were collected. On some of the maps, since the habitat contours clutter the scene, it’s hard even to find the record dot in the first place. For non-native or reintroduced species (eastern fox squirrel, beaver, pronghorn), iNat records will be better than the range maps here, and of course an entry for something like puma will be incomplete if we go by specimens only. What about wolf? There is a recent So Cal record that sadly even has a specimen, but wolf gets no entry. Burro is here but not mustang, tule elk but not the introduced population of Rocky Mountain elk. (This maybe is where an editor would have been helpful?) This book gives an end date of 1906 for So Cal pronghorn, which may reflect museum reality, but if we go by sight records, is off by 40 years. (The last Antelope Valley record I have found is 1946; for reasons I won’t go into here, I think it’s legit.) In some instances, and pronghorn is one of them, Fish and Wildlife data is added onto the maps to fill in for missing specimen data, but it is not consistently followed. I hesitate to bring this up, but prose too often is clunky and redundant — wow, does this book really need an editor — and design too set my teeth on edge. Book design is a skill the same way that residential architecture requires a mix of practical and artistic skills or the same way that building a trail that won’t wash out is a skill, which is something that 99% of self-published authors don’t understand. Writing a technical report is not the same as writing a book (different audiences, for one), and books have conventions that may seem arbitrary but that help enhance communication. There are reasons why a professional designer will get $6,000 to design a single book. (At the very least, I wish first-time authors would read a book ABOUT book design. Some of them are cracking good.) Since it seems to be a print-on-demand product, and since it is 600 full-size pages, I do wish we could have the option of an e-version. The printed version weighs two kilos, so international visitors will be frustrated with trying to pack it for a trip. Some of the pages we could have lived without, like a full page given over to three views of a bobcat skull — one thing that a mainstream publisher will do is to pick a target end size and make the author stick to it. I bring these kinds of things up since we do indeed have self-publishing options now, and given the niche nature of mammal study, there could be many more non-commercial, non-academic, quirky, localized, one-of-a-kind projects yet to come. Who else has a book they would love to share with the world? Lots of us, I hope. Yet for any final product, page layout matters, color matters, font matters — raw content needs to be shaped and modified and presented thoughtfully if it is going to do readers the most good. My editors hold my feet to the fire all the time, and as much as I resent it, in the end they are usually right. This book collates a cornucopia of data, and so hats off to the author for that. The book gets waving victory flags for ambition but more of a squinty face and a shoulder shrug for decisions about how to channel that ambition into a final, in-the-hands product. This project perhaps might work better as a website rather than a hard copy book, or maybe we could have had the maps but not the life histories, since most of us have access to Mammals of the World already. Or maybe I misunderstand and this is trying to guide field surveyors into making more accurate environmental assessments, but in that case, the maps need to be zoomed in on more often, so we can see where the ranges of k-rats begin and end. Maybe 4 or 5 species of k-rat could share the same map, since we have colored dots anyway, and then we could see at a glance if we are in an overlap zone or not. When trying to envision a final product, none of this is intuitive or easy. Hard work, writing, as I have said here before. It is not a pastime I would wish on anybody. None of the famous writers I studied under were very happy people. In grad school if I wanted to meet the people who were laughing around the campfire, I went on the field trips sponsored by the biology department. / Charles Hood, Professor Emeritus, Antelope Valley College (and the author of 20 books, with 2 more in press and 4 more under contract. My head hurts, even thinking about it…..)