Chiapas and Oaxaca, 2024: on the trail of the Tehuantepec Jackrabbit

Tehuantepec Jackrabbit (Lepus flavigularis)

Over the past few years Venkat Sankar and I have been playing tag on our trips to Mexico. Venkat got the ball rolling in 2016 and returned in 2018 and three times in 2019. Inspired by Venkat’s mission to put Mexico on the mammalwatching map I visited, separately, at least once a year between 2018 to 2022. During all of these trips we travelled with Juan Cruzado, a mammalogist who knows Mexican mammals like no one else. But even after so many trips both Venkat and I still had a ton of new Mexican mammals to search for: the country is knee deep in endemics. So in April 2024 we decided to team up for a week with Juan. We picked the southwest of the country, where our main target would be Tehuantepec Jackrabbit: a mammal that Venkat, Juan and I have been drooling over for years.

Tehuantepec Gray Mouse Opossum (Tlacuatzin canescens)

Tehuantepec Jackrabbits are critically endangered. Fewer than a thousand are left, in just one tiny area of central Oaxaca on the shores of a saltwater lagoon. The area has a reputation for being complicated to visit without local help. I remember Curtis Hart went in search of the rabbits a few years ago, only to find a village had blockaded his route, intent on stopping their neighbours from using it after an argument over grazing rights.

We needed local help. Something I left Venkat and Juan to sort out. In fact, Venkat and Juan planned the whole trip. Venkat has an encyclopedic knowledge of Mexican mammals and their distribution. He also remembers every mammal I have seen in Mexico and where I saw it: he knew my hit list better than I did. Once a month they would send me some updates on our plans to which I would reply “sounds great”. The end result was an itinerary that would start in western Chiapas and then into east and central Oaxaca, to search for a diverse set of small mammals. Our trip would culminate with two nights in jactkrabbit habitat. Even Juan Cruzado had not visited most of these sites so this was a voyage of discovery for us all. Venkat was joined by his partner Nicole, who is almost as passionate about rodents and bats as Venkat is. We met in the city of Tuxtla Guttierez.

Tuxtla Gutiérrez

I arrived before Venkat so Juan and I visited the local zoo, which backs onto forest and is home to a wild and reintroduced population of the Critically Endangered Mexican Black Agouti, a species that seems otherwise hard to see. It took us 5 minutes to reach the picnic area where we counted eight animals.

Mexican Agouti (Dasyprocta mexicana)

A family of wild – apparently introduced from Tabasco – Mantled Howler Monkeys (the Mexicana subspecies) were also putting on a show.

Mantled Howler (Alouatta palliata mexicana)

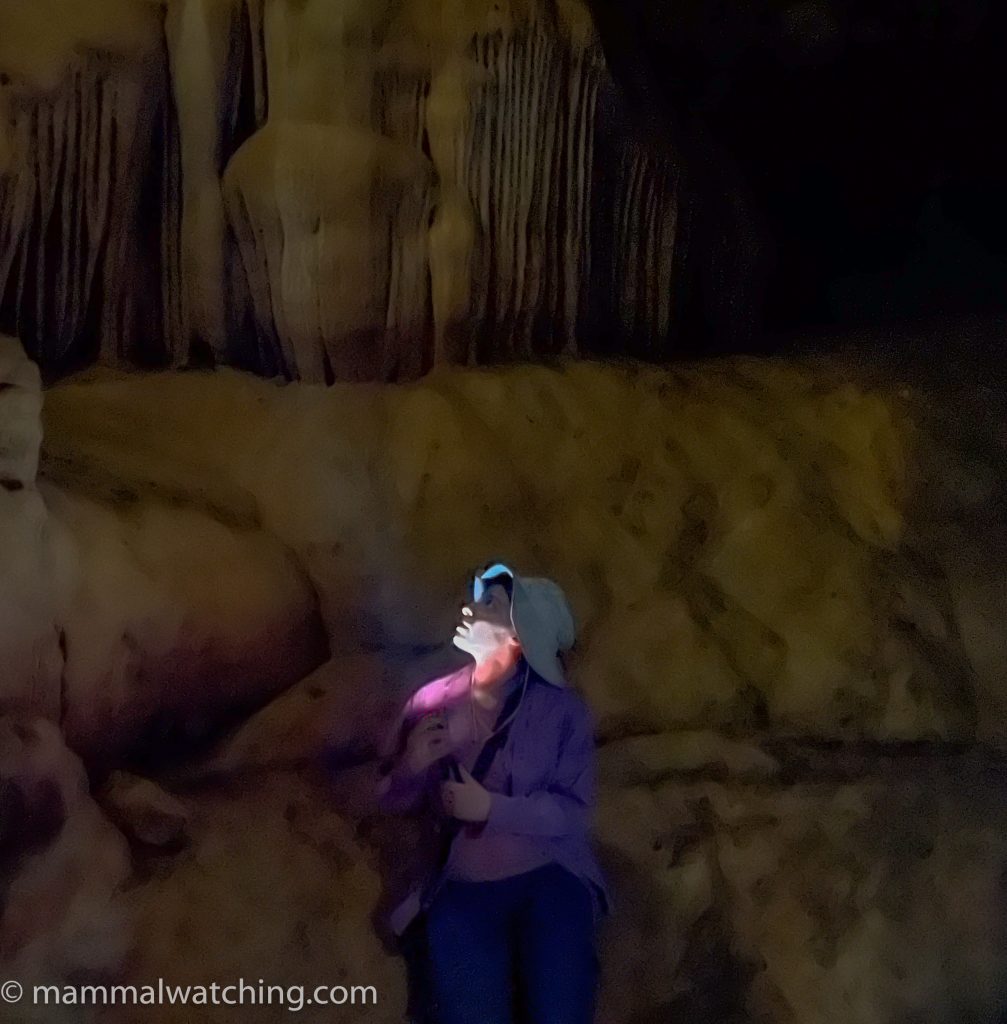

Our next stop was a bat cave just out of town that Juan last visited 25 years ago. The cave is here, though you need to park your vehicle on the side of a busy highway and walk the kilometre to the cave along a faint trail. Pull of the road at the east end of the freeway bridge and the trail begins at the other end of the bridge.

Getting into the cave is not straightforward and requires a 4 metre climb. I chickened out. Juan eventually managed to scramble up there, though the cave was so hot and humid his camera fogged up. It’s home to several species of bats and I wanted to see the large colony of Dobson’s Lesser Moustached Bats that would be a lifer. We arrived just before sunset and right on dusk thousands of bats started emerging, most of which were our target species. I took several hundred abysmal photos (the one below was the best!), to try to get a picture of a bat’s back. The cave is also home to Davy’s Naked-backed Bats, which are a similar size but have a naked back that would be visible in photos from the right angle. Just about every bat I photographed refused to cooperate. The photos also revealed Mexican Funnel-eared Bats.

We had a better look at a few that were flying around a lower entrance hole (on the bottom left of the main entrance) that were clearly Dobson’s Lesser Moustached Bats. We also saw a Greater Sac-winged Bat roosting near the cave entrance.

Dobson’s Lesser Mustached Bats (Pteronotus psilotis) & Mexican Funnel-eared Bats (Natalus mexicanus)

Venkat and Nicole arrived early the next morning and dropped into the zoo to see the agoutis before we headed into the mountains and the small town of Coapilla.

Coapilla

Coapilla, 1400 metres asl, is about five hours’ driving from Tuxtla Guttierrez. Juan enlisted the help of a local environmentalist, Diego Manzano from Pronatura, to accompany us: always a good idea in areas like this to help ensure we stayed in the safe areas. Diego did not want to be paid: he was happy to come along if we covered his expenses.

We stayed in simple cabins on the shores of a lake just outside town called Cabañas De La Laguna Verde. The pine forest near the cabins was bone dry though the vegetation around the lake looked promising for rodents like cotton rats, and Juan decided to try to net bats here. After getting permission from the local managers, we set traps in a better looking patch of forest up the road in a small community reserve, stopping to look at a Red-bellied Squirrel. But here too – like so many places we visited on the trip – the forest was remarkably dry. This seems normal for this time of the year but did not bode well for small mammal activity.

While Juan netted bats we checked out the lake shore with our thermal scopes and quickly saw a Fulvous Pygmy Rice Rat before repeated looks at a Montane Cotton Rat, a local endemic. A night walk along the road in the community reserve produce a Kinkajou.

Back at the lake Juan caught three species of bats.

Toltec Fruit-eating Bat (Dermanura tolteca)

A Toltec Fruit-eating Bat (above) and a Honduran Yellow-shouldered Bat (below).

Honduran Yellow-shouldered Bat (Sturnira hondurensis)

Plus a lovely, and less commonly caught, Broad-eared Free-tailed Bat.

Broad-eared Free-tailed Bat (Nyctinomops laticaudatus)

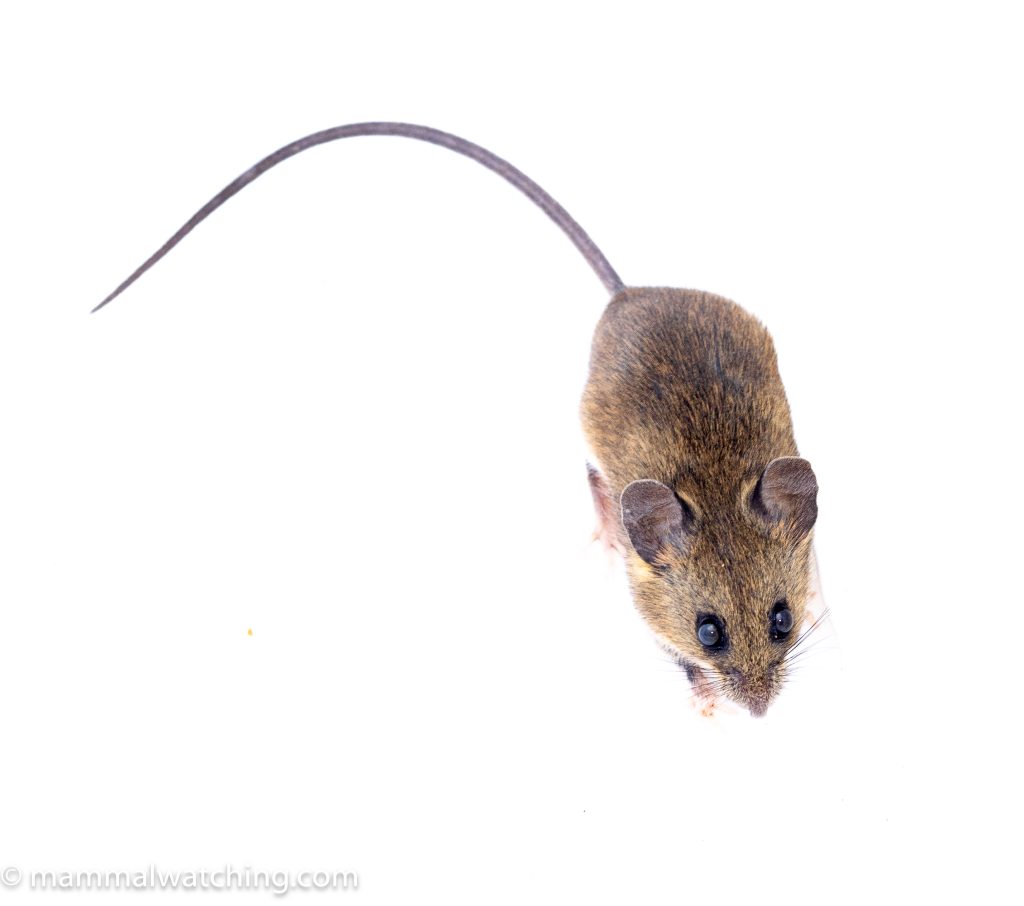

All 70 traps in the forest were empty the next morning: we’d been hoping for Chiapan Deermouse here. But one of our 5 traps by the lake shore held a Montane Cotton Rat, the same species we had seen the night before and a lifer all of us. Juan set up his rodent tent for a photo shoot.

Montane Cotton Rat (Sigmodon zanjonensis)

La Pera

La Pera is a private nature reserve, with a comfortable ecolodge (called ‘Tropatroncos’) about 3 hours southwest of Coapilla and 1000m asl. The reserve is popular with birders and herpers. More importantly it is the type locality of the newly discovered La Pera Climbing Rat (Ototylomys chiapensis). We spent two nights here, trapping small mammals and bats in the forest and walking at night. While the reserve is completely safe we were advised it might not be a good idea to drive around the surrounding area at night.

The forest was dry here and we caught only six rodents over two nights in the small mammal traps. But the diversity of captures was good.

The traps held two Orizaba Deermice,

Orizaba Deermouse (Peromyscus beatae)

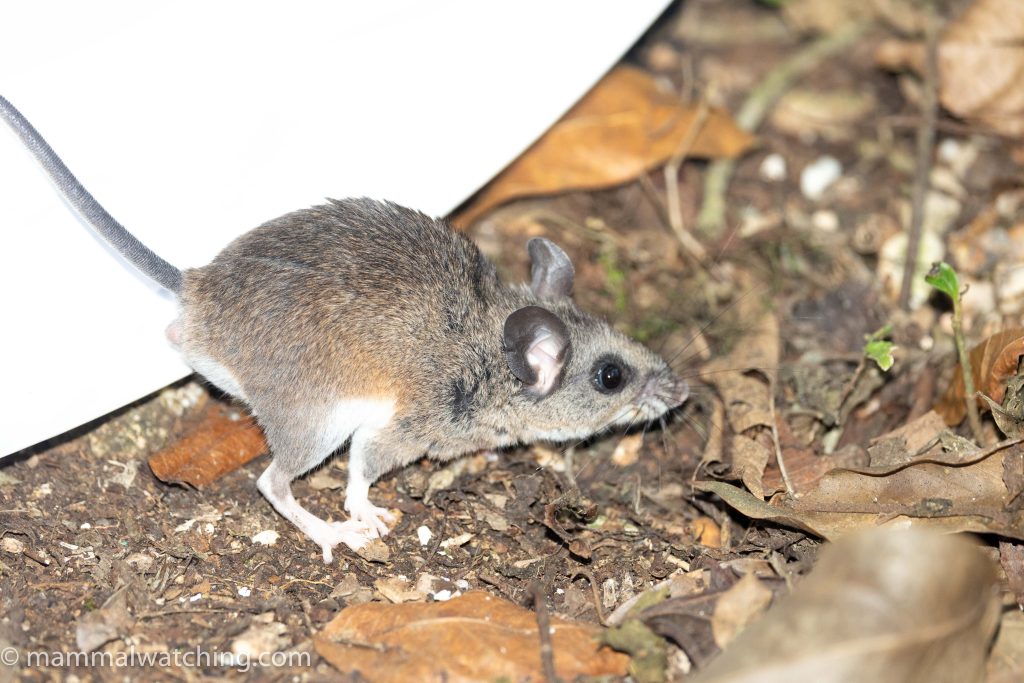

and two Cordillera Deermice.

Cordillera Deermouse (Peromyscus cordillerae)

We also caught a Tehuantepec Deermouse.

Tehuantepec Deermouse (Peromyscus leucurus)

And the owners of the lodge captured this Totontepec Deermouse in their kitchen, which we released in the forest.

Totontepec Deermouse (Peromyscus totontepecus)

Over the two nights Juan captured seven species of bats. The best of which was this Tschudi’s Tailless Bat, another lifer.

Tschudi’s Tailless Bat (Anoura peruana)

We also got a Northern Yellow-shouldered Bat,

Northern Yellow-shouldered Bat (Sturnira parvidens)

a Toltec Fruit-eating Bat,

Toltec Fruit-eating Bat (Dermanura tolteca)

a Mesoamerican Common Mustached Bat,

Mesoamerican Common Mustached Bat (Pteronotus mesoamericanus)

and a Northern Hairy-legged Myotis.

Northern Hairy-legged Myotis (Myotis pilosatibialis)

Juan also caught a few Sowell’s Short-tailed Bats and Jamaican Fruit-eating Bats.

We visited a two caves outside of the reserve, one of which was home to Common Vampire Bats.

Common Vampire Bat (Desmodus rotundus)

The night walks were productive with the help of our thermal scopes and the arboreal rodents we found were happy to pose for photos which made ID possible. This brightly-coloured harvest mouse is a Mexican Harvest Mouse, a lifer.

Mexican Harvest Mouse (Reithrodontomys mexicanus)

While this tiny, and less colourful, harvest mouse appeared to be a Slender Harvest Mouse, also a lifer. Until recently the species was not known from the area, but there is a recent record from Sumidero Canyon, near Tuxtla. Jorge also seemed pretty sure about this ID from our photographs. But it may turn out to be something different, even potentially a juvenile Mexican Harvest Mouse. Time will tell.

Slender Harvest Mouse (Reithrodontomys gracilis)

It froze on a bush and allowed us to get to well within touching range. It was no longer than my index finger.

Slender Harvest Mouse (Reithrodontomys gracilis)

There are lots of boulders in the forest at La Pera and we spent time looking carefully among them for the climbing rats. Though we did not find the endemic Chiapan Climbing Rat we did see two of the similarly large and rare Peters’s Climbing Rats, identifiable by their white-tipped tail. Another lifer.

Peters’s Climbing Rat (Tylomys nudicaudus)

We also saw two Kinkajous.

Kinkajou (Potos flavus)

A lovely spot with great accommodation and excellent food: well worth a visit.

Bahia de Santa Cruz Huatulco

Olive Ridley Turtle

It was a long drive to our next site in the Oaxacan mountains so we broke the journey in the beach town of Huatulco. We drove past hundreds of migrants were walking along the side of the highway: presumably they had crossed into Mexico from Guatemala with another 2,000 miles still ahead of them to the US border. Juan had never seen anything like it.

Though Huatulco was primarily a rest stop there are some good potential mammals here – Pygmy Spotted Skunk are quite often reported for instance – but we were not lucky. Once again the forest was very dry.

Pantropical Spotted Dolphin (Stenella attenuata)

A half-day pelagic trip with Hector Cruz was fun but only produced Pantropical Spotted, Common and Bottlenose Dolphins as well as some distant whale blows that were probably humpbacks.

Common Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops truncatus)

We saw a couple of unidentified mice in the forest around Huatulco at night and Venkat saw a Mexican Cottontail.

This Western Long-tongued Bat was night-roosting in a shelter in Huatulco National Park.

Western Long-tongued Bat (Glossophaga morenoi)

We failed to catch any rodents in a private bird reserve just out of town, though did catch two species of bats: Commissaris’s Long-tongued Bat and Grey Sac-winged Bat. The latter were using the toilet block as a night-roost.

Gray Sac-winged Bat (Balantiopteryx plicata)

Pluma Hidalgo

Pluma Hidalgo is a pretty town, just an hour from Huatulco, and 1400 metres higher. It is popular with tourists looking to escape the heat, enjoy the coffee and take in the views. We spent a night at the very comfortable cabins at Finca Don Gabriel. The mammalwatching was quite disappointing and it was difficult to find places to set traps or set bat nets. We didn’t catch any bats but did find maternity colonies of both Merriam’s Long-tongued Bats and Seba’s Short-tailed Bats night roosting under a bridge near town.

Merriam’s Long-tongued Bat (Glossophaga mutica)

There was only one rodent in our traps the next morning though it was a good one: the local and beautifully distinctive annectens subspecies of Painted Pocket Mouse.

Painted Spiny Pocket Mouse (Heteromys pictus annectens)

The animal was more richly coloured than others I have seen and seems destined to be split.

Painted Spiny Pocket Mouse (Heteromys pictus annectens)

San Miguel Suchixtepec

Juan and two deermice lifers

Our next stop, near Suchixtepec, was 2 hours – and more than thousand metres higher -into the mountains. We set traps(here) in cloud forest that had actually seen some rain in the past few weeks and looked far more promising that our other trap sites.

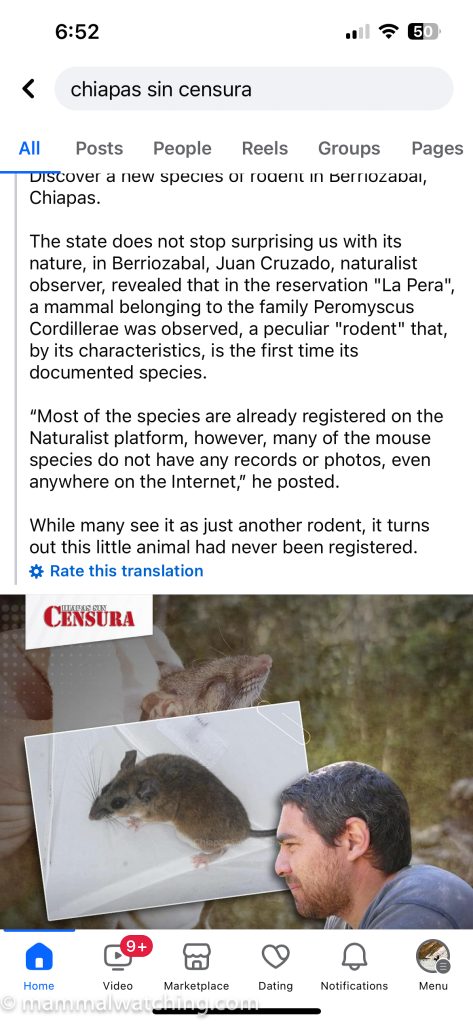

We spent the night in some cabins at a trout farm – Rancho San Melchor – up at 2400m asl. During dinner Juan discovered one of his facebook posts about our Cordilleran Deermouse capture in Chiapas had been rewritten by a Facebook group “Chiapas Sin Censura“. Unfortunately, their lack of censorship seemed linked more to promoting incompetence than freedom of speech: Juan’s post had reported the first iNaturalist record for the species in Chiapas. Chiapas Sin Censura said he had discovered a brand new species, with Juan Cruzado now ‘Juan Carlos’ and portrayed in the – presumably AI generated photo – by a male model. Most of the thousand plus comments were comparing the local politicians with the local rodents. Juan is probably now on a political hit list. I am still laughing.

Fake Juan

It was almost chilly up there but a short stroll after dark in the forest turned into two hours featuring several arboreal rodents that were hard to get onto. One finally stopped dashing among the branches and we identified it as the little known endemic Oaxacan Highlands Harvest Mouse.

Oaxacan Highlands Harvest Mouse (Reithrodontomys albilabris)

These might be the first pictures ever taken of this species in the wild I suspect: It would be extremely hard to spot without a thermal scope and also hard to live trap too I imagine given how arboreal they are.

Oaxacan Highlands Harvest Mouse (Reithrodontomys albilabris)

We set a handful of traps near our cabin and caught two mice in a woodpile that we struggled to identify. They were too small to be any species from the region other than Orizaba Deermice (Peromyscus beatae), though they looked quite different to the Orizaba Deermouse we had caught at La Pera. After much discussion – and trying to turn our mice into Schmidly’s Deermouse (Habromys schmidlyi) – we decided they must be P. beatae. It seems the animals up here are genetically different to those in Chiapas which explains why they looked different and perhaps one day will become a different species.

If anyone disagrees with our ID please let me know!

Orizaba Deermouse (Peromyscus beatae)

They also liked to climb the sides of the photo tent more than any other mice we captured , something which also hinted that they might be a different, more arboreal species.

Orizaba Deermouse (Peromyscus beatae)

Trapping overnight Iin the damp forest 30 minutes down the mountains was the most successful of the trip. We caught four species, three of them lifers and one with potential to become one.

Guerrero Rice Rat (Handleyomys guerrerensis)

We caught two Guerro Rice Rats and a Fulvous Harvest Mouse (generally regarded as a lowland species the animals up here may be split).

Fulvous Harvest Mouse (Reithrodontomys fulvescens)

Our main targets here were two large and dark deermice species which are quite similar looking. After careful measurements we found we had one of each.

Black-tailed Deermouse (Peromyscus.melanurus)

This, above, is a Black-tailed Deermouse. And below is the slightly larger, and impressively whiskered, Broad-faced Deermouse.

Broad-faced Deermouse (Peromyscus megalops)

Delighted with our three plus lifers we headed back to the coast and then onto Tehuantepec Jackrabbit country.

San Francisco del Mar

It was initially difficult to get information on exactly where to see Tehuantepec Jackrabbits. We knew more or less where they lived, but were advised that we’d need help from the locals to access the right places: strangers stand out a mile in this area. Venkat and Juan were able to track down two local academics, Consuelo and Jorge, who had spent many years working with the rabbits, and were trusted by the local community. They were tremendous. And offered to rearrange their plans to meet us for the weekend and would set up one of their regular monitoring trips to coincide with our visit. Their focus is on saving jackrabbits and they are not tour guides, nor are they yet persuaded about promoting ecotourism in the area. So rather than give more details here if you want to follow in our footsteps you should contact Juan about the possibility of him setting up a visit for you.

Tehuantepec Jackrabbit (Lepus flavigularis)

We stayed in the small town of San Francisco Del Mar. Very few people visit. It is the sort of place where google maps leads to the next town across a very real river via a bridge that doesn’t exist.

We had expected to stay with a local family before discovering there was a hotel in town. Also not on google maps. We picked up our room keys from a shoe shop and drove to the hotel but couldn’t find it. Back at the shoe store the holder of the keys sent her daughter ahead of us on a moped to show us the hotel: she waved in the direction of a building and rode off. Five minutes – and 25 failed attempts to use various keys on various doors – we found our rooms. It was actually quite comfortable once we turned on the AC for an hour: you could have cooked pizzas in the windowless brick rooms when we first arrived. But my almost 5 start review took a turn from the worse when the water ran out a couple of hours after we arrived. The shoe store people turned it on again the next day but it mysteriously dried up again an hour later.

But if you cannot take a shower in your San Francisco del Mar hotel do not be concerned. Over breakfast the next morning, the owner of the tiny cafe was excited to meet people from out of town, let alone from out of Mexico. She asked Juan where we were staying and if it was OK. Juan explained the lack of water. She invited all of us back to her place for a shower. It is that kind of a town. In fact all the local people we met there were about as friendly as I have ever met anywhere. They could not do enough for us and were delighted by our interest in the local fauna.

Jorge and Consuelo looking for jackrabbits via drone

We spent two nights in the back of the researchers’ pickup spotlighting for jackrabbits and other animals. It was productive. We saw about 15 Jackrabbits over the two evenings. They were the most commonly encountered mammal and relatively easy to approach.

Tehuantepec Jackrabbit (Lepus flavigularis)

We also saw several of the distinctive aztecus subspecies of Eastern Cottontail.

Eastern Cottontail (Sylvilagus floridanus aztecus)

Other mammals included a Nine-banded Armadillo, Common Opossum and Northern Raccoons.

Nine-banded Armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus)

As well as this Grey Fox.

Northern Gray Fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus)

The area has an extraordinary density of skunks. Driving the few kilometres from the jackrabbit site to our hotel each night produced 10 Hog-nosed and 10 Hooded Skunks!

American Hog-nosed Skunk (Conepatus leuconotus)

Hooded Skunk (Mephitis macroura)

As well as a gorgeous Tehuantepec Gray Mouse Opossum that Venkat spotted with a thermal scope.

Tehuantepec Gray Mouse Opossum (Tlacuatzin canescens)

During the day we tried searching for the jackrabbits by drone but it was too windy to fly the thing properly.

There are some very cool rodent records from the area but we didn’t catch anything overnight in our traps. There are some good bats here too and it sounded like the fantastic Wrinkle-faced Bat is not uncommon, though we did not find one..

We did fine a lone Lesser Long-nosed Bat roosting in a well in front of an abandoned farmhouse.

Lesser Long-nosed Bat (Leptonycteris yerbabuenae)

Juan and Nicole set up bat nets on our second night. While they were setting traps the local guy who accompanied them saw a Jaguarundi walk in front of the car. They are also not uncommon in the area it seems.

We caught two exciting bats.

Davis’s Tent-making Bat (Uroderma davisi)

First, was a Davis’s Tent-making Bat a new species for usl.

Slender Yellow Bat (Baeodon gracilis)

Second was a small yellow bat that we identified as a Northern Yellow Bat. Back home Juan was checking his notes and realised this bat had a forearm too long to be this species. It’s 33mm forearm, plus large ears, made it a Slender Yellow Bat, a lifer for all of us. The perfect postscript to a great trip.

Slender Yellow Bat (Baeodon gracilis)

Final thoughts and thankyous

This was my tenth trip to Mexico and once again it delivered a lot of new mammals (17 and counting), fabulous food and friendly people. I see many more trips in my future. There is no doubt that some areas of Mexico are dangerous but the perception some have that the country is generally unsafe for travel is simply not true. With Juan’s help it seems perfectly safe so long as you know exactly which areas to avoid.

We travelled at the height of the dry season. This might have been better for some of our target species but I suspect that small mammal trapping would be more productive at the start or end of the rainy season. So there is still plenty to return for in this region – there must be another 15 lifers at least that we missed. It is also worth noting that some of the species we found on this trip are barely known outside of a scientific paper or two: we may have taken the first live photos ever of several rodents. And video too: Nicole created this 10 minute montage of rodent porn (and if you found this page after Googling ‘rodent porn’ then this might not be what you were hoping for. Huge mistake: I just Googled that term and really wish I hadn’t).

Thank you to my travel companions, Venkat and Nicole, with additional thanks to Venkat for applying his supercomputer of a brain to masterminding our route. Thanks to Randy Babb for helping connect us to the jackrabbit researchers, to Diego in Chiapas, to Jorge and Consuelo in Tehuantepec, as well as the local community there for welcoming us with open arms. And, of course, thanks again to Juan ‘Carlos’ Cruzado for his good humour, expertise and tireless energy.

Trip List

Northern Black-eared Opossum (Didelphis marsupialis)

Virginia Opossum (D.virginiana)

Tehuantepec Gray Mouse Opossum (Tlacuatzin canescens)

Nine-banded Armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus)

Mantled Howler (Alouatta palliata mexicana)

Tehuantepec Jackrabbit (Lepus flavigularis)

Eastern Cottontail (Sylvilagus floridanus aztecus)

Mexican Cottontail (Sylvilagus cunicularis) (Venkat only)

Mexican Agouti (Dasyprocta mexicana)

Red-bellied Squirrel (Sciurus aureogaster)

Painted Spiny Pocket Mouse (Heteromys pictus annectens)

Orizaba Deermouse (Peromyscus beatae)

Cordillera Deermouse (P.cordillerae)

Tehuantepec Deermouse (P.leucurus)

Broad-faced Deermouse (P.megalops)

Black-tailed Deermouse (P.melanurus)

Totontepec Deermouse (P.totontepecus)

Oaxacan Highlands Harvest Mouse (Reithrodontomys albilabris)

Fulvous Harvest Mouse (R.fulvescens)

Slender Harvest Mouse (R.gracilis)

Mexican Harvest Mouse (R.mexicanus)

Guerrero Rice Rat (Handleyomys guerrerensis)

Fulvous Pygmy Rice Rat (Oligoryzomys fulvescens)

Montane Cotton Rat (Sigmodon zanjonensis)

Peters’s Climbing Rat (Tylomys nudicaudus)

Gray Sac-winged Bat (Balantiopteryx plicata)

Greater Sac-winged Bat (Saccopteryx bilineata)

Mesoamerican Common Mustached Bat (Pteronotus mesoamericanus)

Dobson’s Lesser Mustached Bat (P.psilotis)

Seba’s Short-tailed Bat (Carollia perspicillata)

Sowell’s Short-tailed Bat (C.sowelli)

Common Vampire Bat (Desmodus rotundus)

Tschudi’s Tailless Bat (Anoura peruana)

Commissaris’s Long-tongued Bat (Glossophaga commissarisi)

Western Long-tongued Bat (G.morenoi)

Merriam’s Long-tongued Bat (G.mutica)

Lesser Long-nosed Bat (Leptonycteris yerbabuenae)

Jamaican Fruit-eating Bat (Artibeus jamaicensis)

Toltec Fruit-eating Bat (Dermanura tolteca)

Davis’s Tent-making Bat (Uroderma davisi)

Honduran Yellow-shouldered Bat (Sturnira hondurensis)

Northern Yellow-shouldered Bat (S.parvidens)

Broad-eared Free-tailed Bat (Nyctinomops laticaudatus)

Mexican Funnel-eared Bat (Natalus mexicanus)

Northern Hairy-legged Myotis (Myotis pilosatibialis)

Slender Yellow Bat (Baeodon gracilis)

American Hog-nosed Skunk (Conepatus leuconotus)

Hooded Skunk (Mephitis macroura)

Kinkajou (Potos flavus)

Northern Raccoon (Procyon lotor)

Northern Gray Fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus)

Common Dolphin (Delphinus delphis)

Pantropical Spotted Dolphin (Stenella attenuata)

Common Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops truncatus)

54 species and 17 lifers, plus a Jaguarundi (Herpailurus yagouaroundi) seen only by a local guide.

Post author

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.