Ladakh, 2014

Blue Sheep, Pseudois nayaur, Hemis National Park

Snow Leopards are one of the most enigmatic of all animals. For me, like for many of us, they symbolise the truest of true wilderness. Their rarity, beauty and downright coolness makes them an extremely sought after mammal and they have always ranked as the top of my most wanted list. Indeed I can’t imagine there would be many mammal watchers who wouldn’t put them in their Top 10 to See List.

For the first 20 years or so of my mammal watching career the chance to see one was but a distant dream: I remember talking to an Australian in 2000 who had spent three years studying them in Nepal and never seen one in the wild. In fact it wasn’t until I first corresponded with Richard Webb in 2006 that I talked to someone who had ever seen one (see his Kazakhstan Trip Report). And then a few years ago an animal took up residence for years running in the depths of winter near Chitral, Pakistan but I couldn’t make those trips. In 2009 I came close to seeing one in Kyrgyzstan, on a fabulous trip, and I also had a vague hope I might see one during a weekend in Pakistan in 2010 but did not get close.

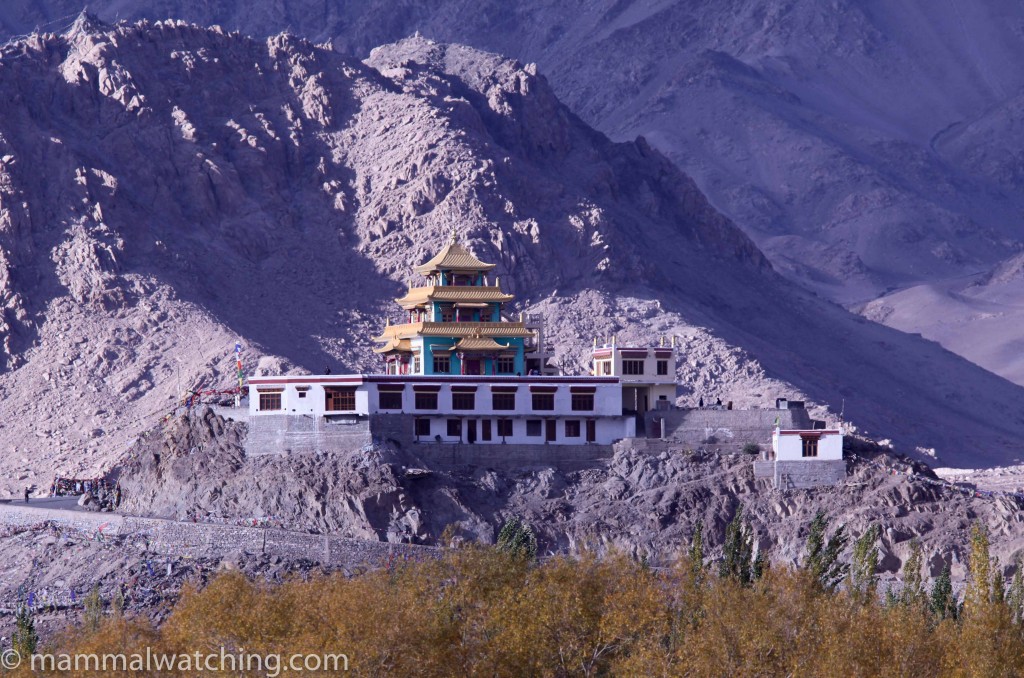

Snow Leopard habitat near Leh

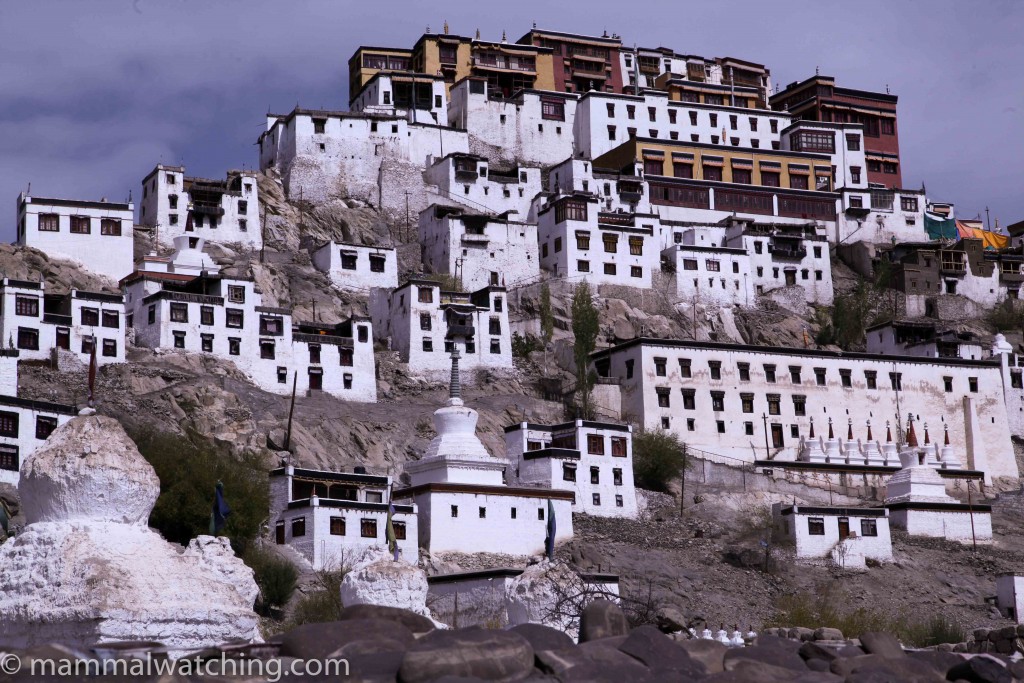

Fortunately over the last few years Hemis National Park in Ladakh has emerged as the Snow Leopard capital of the world. A cottage industry has sprung up around the animals and each year several hundred people pay several thousand dollars each to camp in sub-zero temperatures, at an uncomfortable altitude, to stare all day at distant cliffs. Such is the draw of Panthera uncia.

I’ve wanted to visit for several years but it wasn’t until 2014, while watching the end of the Secret Life of Walter Mitty, that I decided the time had come. If Sean Penn can see a Snow Leopard then so can I.

In truth it did cross my mind that that movie might generate even more traffic to Hemis which in turn might prompt the Indian Government to limit access to the park. And if that happened before I visited I would be kicking myself for ever more. So I emailed Phunchok Tsering from Exotic Travel in Ladakh (who also has a second website focussed on Snow Leopard trips). Five months later I was sitting on top of a ridge staring at a Snow Leopard.

“Blow horn on my curves”. Wasn’t that a movie…?

When to go?

Winter is undoubtedly the best time to see Snow Leopards. But it is also the least comfortable. I don’t think anyone tries in December or January – it is just too bloody cold – and so peak season is late October or late February/early March. I decided to try early October because I hoped there would be fewer people in the park; other wildlife might be a bit more active (there might still be a chance of seeing marmots for example); and because the guides are getting better and better at finding animals throughout the year.

Richard Webb advised me to use Exotic Travel and I dealt with the owner Phunchok Tsering. He was extremely helpful, knowledgeable, always quick to respond and a thoroughly nice guy. He was also super flexible and patient with our group when we arrived as we changed our plans pretty much daily. I cannot recommend him highly enough.

It would be an expensive trip to do alone so I decided to organise a small group of fellow enthusiasts and very quickly we were seven: most of whom I knew – or felt I knew – quite well already. Tomer Ben-Yehuda (Israel), Charles Foley (Tanzania), Kate Goldberg (UK), Morten Joergensen (Denmark) and two others. This well-travelled bunch had an impressive mammal and country list between them and a huge deal of experience looking for wildlife.

Before a day to day account of the trip I think it is useful to provide some general information about the park, the day to day life in camp, and how to look for Snow Leopards and the mammals in different areas.

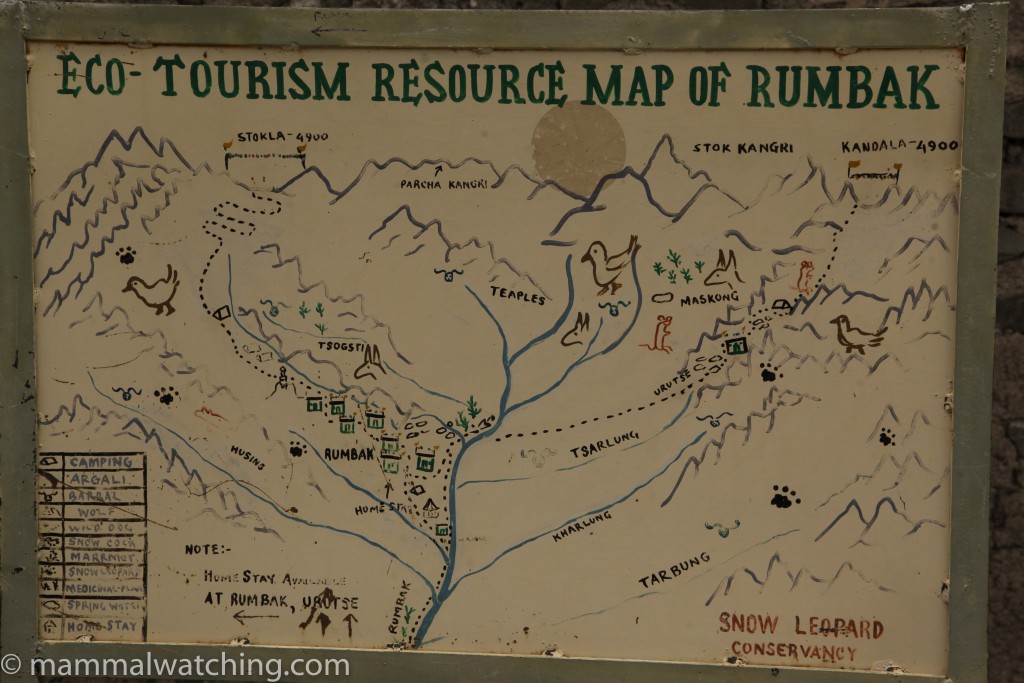

Hemis National Park

At 4,400 square kilometres Hemis is India’s largest national park, and the only national park within the Palearctic faunal zone. Current estimates suggest there are nine Snow Leopards using the park permanently plus another two occasionally venturing in. And yet there are only two park rangers! One of whom, Smanla, was our guide for the trip (he takes vacation from his day job to guide occasional Snow Leopard groups). Smanla is an exceptional guide and an exceptionally good guy. More on him later.

Rumbuk Valley, Hemis National Park

In Winter 2013/14 about 300 people visited the park specifically to look for Snow Leopards and during late Feb 2014 there were nearly 200 tourists, porters and guides camped in the park. This overcrowding has prompted the park to start limiting the number of tourists to a maximum of 50 at any one time. Hemis is also a popular trekking destination, particularly in summer: there were still a few hardy German and Swiss trekkers walking around in October.

Life in Camp

Although there are a few homestays in the park, most Snow Leopard tourists camp. There are several campsites. Most people stay – or used to stay – at the lower campsite in the Rumbuk Valley. This campsite was shut when we visited, because a new road is being constructed and they were blasting near camp. And so we stayed another hour and a half’s walk up the Rumbuk Valley, near to Rumbuk Village. Other homestays and campsites are dotted around but they are further from the leopard spotting epicentre.

Rumbuk Valley campsite

The camp routine began at first light where we would join the spotters on a nearby ridge or hill for a couple of hours of pre-breakfast spotting. The guides would then hatch a plan for the day, which meant typically a day hike in search of Snow Leopards, returning to camp in the mid-afternoon. Lunch was usually portered over to us. We’d spend the last two hours of the day scanning for Leopards near camp. If anyone managed to stay awake later than 8.30 p.m. it was a talking point for days to follow.

The camp staff makes life as comfortable as possible. Hot water is always available for washing, though “washing” seldom extended beyond my hands and face. Only in the middle of the day was it warm enough to contemplate taking off enough clothes to wash other bits of me. But in the mid-afternoon we were usually out in the park looking for leopards. Having said that, the climate was so dry and cold that sweat is a rarity: not washing for a week isn’t as gross as it sounds. Not quite anyway.

The food was extremely impressive for a camp kitchen and included loads of delicious local food, pizza, industrial quantities of eggs each morning, and a Snow Leopard cake on our last night.

Altitude and Cold

Hemis ridgelines

Most of the Snow Leopard action in Hemis is at about 4000 metres. Everyone noticed – and nearly everybody suffered from – this altitude. Any exertion is tough,. Plusit is generally harder to sleep and when sleep comes it came with vivid dreams (well it did for me). We were also a sickly bunch. I’m not sure whether the height increases the chance of other illness, or just aggravates the symptoms, but most people were sick for a day or so during different bits of the trip from various ailments. So far we all remain alive.

The first half of October was also a bit colder than I was expecting: night-time temperatures were often below -10C and on several nights my water bottle froze solid inside the tent. Days could be relatively warm and I even took my jacket off on two separate afternoons. But as soon as the wind started to blow – which it did every three minutes and/or as soon as Charles took his jacket off – the temperature would drop by 10 degrees.

Looking for Snow Leopards

Here kitty kitty, here kitty kitty

Hemis has a healthy population of Snow Leopards. They may also now be less wary of people than in some other parks and we were told there has been no conflict between people and the animals for a generation. But still there are only nine animals across a four and a half thousand square kilometre slab of the Himalayas. So you won’t be falling over them.

A key advantage of the park are the excellent spotters and guides who have enormous expertise now in finding the animals. Those we met were exceptionally hardworking with superhuman powers of concentration. Their approach was to focus their scope intently on a section of the landscape for several minutes before moving to a different area. This allowed them to spot leopards several kilometres away. I took more of a shotgun approach, like a drunk at a roulette table, randomly pointing my binoculars or scope in a lucky direction and hoping for the best.

Kate, Charles & Morten take a break from scope duty

Each tourist group typically has a guide and one or more spotters. They all share information – communicating by radio – and so the more groups the more guides and the more the merrier.

The guides advised us to focus attention on ridge lines, the usual routes by which Snow Leopards travel, and to focus our efforts during the first two or three hours post dawn and pre-dusk. Of course leopards move at other times and in other areas, but 90% of sightings are made at these times. My advice would be not to second-guess the guides and stay close to them always. They make 90% of the sightings (despite being outnumbered six to one by tourists) and have an almost second sense in their understanding of the leopards movements around the park.

The Snow Leopard Trust have a useful factsheet on the beast.

Mammals

We visited three different areas and each has a different set of mammals.

Leh

Our first couple of days were spent in and around Leh where we were “resting”. Pikas, I am not sure which species, are occasionally spotted by the Indus River near town in one of the areas the guides often visit looking for Ibisbills or Solitary Snipes. We didn’t see either bird or any pikas.

Leh suburbia

Ladakh Urials can often be tracked down on the hillsides a few kilometres outside of Leh on the main road to Nimmoo. Phunchok found a couple of groups for us in the late afternoon.

We also went spotlighting outside of Leh, in the same area at the Urials, and apparently were one of the first groups to have done so. Despite the habitat looking like a barren wasteland we had a surprisingly good night finding a pack of four beautiful Wolves, several Red Foxes and a couple of Woolly Hares in just two hours looking. We also saw a couple of (probable) House Mice at the monastery just outside town.

Mountain Weasels are sometimes spotted in or around town though we couldn’t rustle any up despite enthusiastic squeaking near every stone wall.

Hemis National Park map

Rumbuk Village Area (Hemis National Park)

We saw our first Blue Sheep on the walk up the Rumbuk Valley after the lower campsite. We could always see at least one group from anywhere higher up the valley though sometimes they would take a bit of intensive scoping to seek out.

Blue Sheep, Pseudois nayaur

Large-eared Pikas are easily seen at “Pika Point”, a section of boulders along the river not far after the first campsite as you are heading towards Rumbuk: cross the first wooden bridge after the campsite and the trail bends to the left. The pikas are in the rocks immediately after the bend. After much discussion I am pretty sure we didn’t see any Royle’s Pikas here.

Snow Leopards could be anywhere and we also spotted a Wolf twice from our campsite. Mountain Weasels were seen several times around Rumbuk Village and once in the middle of our campsite during our stay, while a Stone Marten visited camp each night looking for food after people had gone to bed. It was extremely bold approaching people on Marten stakeout to within a metre. We also found a different pika species – Nubra Pika – living in the bushes along the highest fence line that bordered the fields next to camp (this is the fence line that one has to walk past on the way back down the valley).

Mountain Weasel, Mustela altaica

Though many people have reported Royle’s Pika in trip reports we didn’t see any. Nor did we see Woolly Hares in this area, though in February they have been reported from the small plantation area immediately above the lower campsite.

Kandala Pass Base Camp Area (Hemis National Park)

Some of our group spent a couple of nights in the Yurutse Homestay, a 90 minute walk from Rumbuk village on the way to Kandala Pass. This was a base for us to search for lynx around the two campsites a further 30 and 60 minutes respectively up the Yurutse valley towards Kandala.

Spot the lynx

We didn’t see a lynx although I suspect with four or five days up there, with intensive spotting, we could have. We did see Wolf twice (more common here than nearer to Rumbuk apparently), several Woolly Hares (very common between the two campsites), Mountain Weasel twice at the upper campsite,.

Long-tailed Marmotsand what I think are Silvery Mountain Voles are abundant a little earlier in the season: indeed I think the marmots only hibernated a few days before we arrived on 13 October. There is also a reasonable chance to see Argali from the top of Kandala Pass though the walk up to the point – nearly 5,000m high – would have been a challenge for me.

The Day to Day Account

Sunday October 5: Leh

Our group all flew into Leh on a Jet Airways flight from Delhi, landing, as all flights to Leh do, in the early morning. The view from the plane on the left hand side was spectacular. It might have been even more spectacular on the right (though the rising sun was also blasting from that direction).

The Himalayas

Leh is not a typical Indian city: it is small, it is clean and it is quiet. Indeed I soon realised that many Ladakhis do not consider themselves to be Indian at all. And so ten minutes after leaving the plane we were drinking tea and waiting for breakfast in sunshine in the garden of the Lotus Hotel.

Leh – India’s best kept town?

Standard practice on these trips is to spend a couple of days resting in Leh to acclimatise to the 3,500 metre elevation. The altitude was more than noticeable so I think it would be a mistake not to take a couple of days rest before heading to the park.

After a morning napping we spent the afternoon looking for Ibisbills and Solitary Snipes along the Indus river a few kilometres out of town. Once I learned there were also pikas living in the same area most of us diverted our efforts towards the mammals and away from the birds. But despite three hours looking we didn’t find pikas or either species of bird. There were, however, a lot of Sunday-afternooning locals lounging around in the same area that didn’t help our efforts.

Whenever I arrive in a new area on a trip I usually find my expectations change after a first conversation with the locals. Often, expectations are raised quite sharply with a first day buzz that comes from talk of some species not anticipated. Typically these heightened expectations slowly subside during the remainder of the trip when the unanticipated species fail to materialise and I end up seeing pretty much what I had expected before I arrived. Alternatively, expectations are lowered when various problems emerge. This is what happened today, when Phunchok explained that a new road that was being built into the Rumbuk Valley, right up to Camp Snow Leopard. This sounded like it could have all sorts of implications for the future of Snow Leopard watching. But, more immediately, the blasting going on for the road’s construction meant the usual Snow Leopard camp site – strategically positioned at the head of three key valleys – was out of bounds. Instead, we would have to camp higher up the valley. Our optimism was lowered a little. But it is what it is: and we took solace in realising that we’d made a wise choice in not postponing our trips any longer.

Bridge near Leh

We hung a spotlight out of the car window on the way back to the hotel. Both Red Foxes and Wolves might be possible here though we didn’t see anything other than countless stray dogs.

Monday October 6: Leh

Our second and final rest day in Leh started early for some of us with a return to the sites along the Indus to look for Ibisbills, Solitary Snipes and, more importantly, pikas. We didn’t see any though the view was worth the early start.

Indus Valley

After breakfast we visited a monastery 10 km out of town. This was ostensibly a cultural excursion but I remember that Dominque Brugiere had seen a Mountain Weasel here. So most of us hung around the parking lot and the gardens looking for weasels rather than going inside. Mammals 1: Culture 0. It was, apparently, very nice inside. Phunchok was beginning to realise just how focussed on mammals we were.

Weasel habitat

Charles spotted a mouse in the scrub below the monastery. We got only the briefest views and suspected it was a House Mouse. Morten also saw a mouse inside, feeding on grain spilled by messy monks.

We ran in to Michel Gervais (frequent contributor to mammalwatching.com) and his wife outside the monastery. They too were in town for the Snow Leopards and it was beginning to feel like the entire mammal watching community were on a Snow Leopard haj.

After a visit to the only working Internet cafe in Leh (floods in Kashmir a month ago had knocked out the whole town’s Internet) we drove 45 minutes along the main road west (towards Kashmir) to look for Ladakh Urials. Half an hour before sunset we found a group of 26 and – after a short but steep hike – were able to get within 300 metres of them. The first non-mouse mammal of the trip, and one I was happy to see in Leh as they are uncommon in the park. Some treat Urials as conspecific with Moufflon but to me at least they looked sufficiently different to be treated as a separate species, Ovis vignei.

Ladakh Urial, Ovis vignei

After dinner Phunchok offered to take us back to the same area for some spotlighting. The road leads on to his village – Nimmoo – and he often sees foxes and Wolves late at night on the drive. I was more than a little sceptical about the prospects of seeing anything in the barren hills, but I had brought a spotlight for just this reason and we decided to give it a go. I was wrong. We had a great couple of hours along the road, starting with a prolonged look at four very large and very healthy looking Wolves. This was my best Wolf sighting ever. They refused to be lured in by Charles’s howling, but were in no hurry to leave either (though they were quite distant and only Tomer managed a blurred photo with his super zoom).

Distant Wolf pack. Picture Tomer Ben-Yehuda.

Five minutes down the road, and high on a hillside, we saw a mystery animal, quite probably a Red Fox. We saw at least another four Red Foxes that evening. The last new species of the night were two Woolly Hares on a hillside close to the road. A lifer for most of us, and though we would probably also see them in Hemis it is always great to knock species off the list early on.

We got back to the hotel at 12.30 a.m. So much for our rest day.

Tuesday October 7: Leh to Rumbuk

We left Leh at 9.30 a.m. for the scenic drive to Zinchen, in Hemis National Park. It is less than an hour’s drive though we stopped to take pictures and continue our search for the elusive Ibisbills. They remained elusive. Phunchok stopped at small shrine near the park entrance to make an offering to the Snow Leopard gods (cooking oil appears to be the divine currency of choice). As we stopped a couple of Wolves howled in the distance.

Phunchok makes an offering

At the end of the road we met Smanla, who was to be our guide for the next ten days. A mule train took our bags and we set off on the slow three hour walk to our campsite next to Rumbuk village. It was a gentle but steady climb (we probably gained about 500 metres over 5km) and we walked slowly in the autumn sun. Spectacular views were everywhere.

We stopped for lunch just beyond the lowest campsite and had spotted at least two Large-eared Pikas running through the rocks. A second lifer for me.

While the soup was served we spotted four beautiful Blue Sheep on the cliffs. The second lifer of the lunch break.

Blue Sheep, Pseudois nayaur

The last hour of the walk produced more Blue Sheep and another Large-eared Pika.

Our campsite – at the junction of the Rumbuk and Tsarlung Valleys – was perfect, right down to the purple flysheets covering floral tents. Camp in both senses of the word.

Rumbuk Camp

We were sharing the site with Karl Van Ginderdeuren and his group from Europe’s Big 5. We were envious of their spotting scopes and macho tents.

After we had had the first of the 1000 cups of instant coffee our group would drink that week, both groups joined their respective guides and spotters on the ridge 20 metres above camp to spend the rest of the day scanning ridges for Snow Leopards.

Scanning for Snow Leopards, Rumbuk camp

The general theory is that Snow Leopards:

- move only in the early morning and late afternoon;

- are almost impossible to spot when stationary; and

- travel primarily along ridges.

Our campsite was strategically position with many ridges in view that separate several valleys habitually used by Snow Leopards. We heard that the last tourists – who’d left two weeks before we arrived – had seen a Snow Leopard from the campsite on their last night. And a week before we arrived, villagers had found a fresh Blue Sheep kill a few hundred metres away. So Leopards were using the area, but would we see them? When we looked at the vast slab of park in front of us the task was daunting.

As the sun dropped below the peaks the temperature plummeted, not helped by an icy wind, and nearly everyone made a dash back to the tents to add several layers of clothing. We kept scanning until just before 6 p.m. but the only mammals were groups of Blue Sheep scattered over the mountainsides.

Dinner was waiting when we got back. The whole camp was asleep by 9.30 p.m. though I didn’t realise that this would be, in fact, a late night by camp standards.

Wednesday October 8: Rumbuk Camp

To peevaricate: to lie in a cold cold tent in the early hours of the morning, wanting to urinate but resisting in the futile hope that the urge will pass. It doesn’t.

I didn’t sleep brilliantly though discovered I had slept better than anyone else in our group or Karl’s for that matter. Several of us were sick with various ailments, all no doubt exacerbated by the altitude and the cold.

Our first full day in Hemis and the campsite routine was established. From 6 a.m. – 8.30 a.m. the spotters stay close to camp looking for leopards. Over breakfast they hatch a plan for the rest of the day. At 9.30 a.m. we headed up the Tsarlung Valley for two or three km. But the gentle gain of 300 metres still made for a tiring hike at this altitude. Even lying down was tiring! Blue Sheep were visible throughout the day but that was the only mammal we saw.

Blue Sheep, Pseudois nayaur

Lunch was delivered to us in the valley, and we returned to camp mid-afternoon to spend the last two hours of the day scanning from a ridge near camp. I was now wearing four layers of clothing and the temperature was bearable. Sleep by 9 p.m..

Thursday October 9: Rumbuk Camp

Scanning from the hill next to camp at dawn produced a lot of Blue Sheep but no leopard. But at the end of breakfast our talented chef let out a cry of “weasel” and we had the most wonderful views of a Mountain Weasel running in and out of the rocks next to camp for a good 10 minutes. A really lovely animal.

Mountain Weasel, Mustela altaica

The other group decided to head lower down the valley, to the Tarbong and Husing Valleys, to look for leopards. We made a short but perilously steep climb up the side of the Kharlung Valley. Great scenery as always and a lot of Blue Sheep – one group numbered 26 – but no leopards. The guides communicate by walkie-talkie and a radio call came through after lunch to say that Jigmet, the guide for the other group, had found very fresh signs of a Snow Leopard at the entrance to the Husing Valley (it appeared to have walked through the former campsite). We hoofed down and saw more pikas. But no one saw a Snow Leopard.

Tonight marked the end of what was only our second full day of looking. Before we arrived in camp none of us had seriously expected to have seen a leopard in the first two days. Nevertheless a sort of collective – and viral – angst took hold during dinner. Were we too high? Too low? Should we hire more spotters? Should we split up to spread our efforts? Or stay in camp close to the radio receiver?

I for one thought it best to put our faith in Smanla and Jigmet, the guides. Not only did they seem to want to see the animals almost as much as we did but they had over 30 years’ experience between them in looking for them. But we remained nervous. So we politely asked Smanla what we might do to improve our chances: a conversation I imagine he must have, later – or more usually sooner – with every group he guides.

He conferred with Jigmet and returned with a smile to say they had decided that we should get up at 5.15 a.m. and climb the “small hill” behind camp. At 4,000m no hill seems small. This one looked enormous. And so, somewhat anxious about the next morning, we took our hot water bottles to bed at 8 p.m.

Friday October 10: Rumbuk Camp

Several of us heard a strange bird-like sniffing around camp at 3 a.m. Smanla said it was a Beech Marten. Tomer, who was about as desperate as anyone has ever been to see a Beech Marten, vowed to get out of bed if he heard another one.

The 5.15 a.m. wakeup call was not as brutal as I’d feared: most of us had already had eight hours sleep by 4 a.m. It was cold though and the climb up the “small” hill had me wondering whether my heart might actually burst. The view from the summit was as mind-blowing as ever and thankfully there was no wind. We spent a couple of hours scanning ridge after ridge after ridge: plenty of Blue Sheep but no sign of a leopard. Then Jigmet’s radio crackled with an Australian voice.

Garry Deering, an Aussie, had been walking the hills of Rumbuk alone for the past week. He too was looking for Snow Leopards and apparently, unlike the rest of us, never got out of breath (he’d bounced past us on the trail the day before). Whatever he said to Jigmet on the radio was important: Jigmet ran down the ridge then ran up again announcing that a Snow Leopard was on the mountainside directly opposite us. I don’t think any of the 20 scopes up on the top of our hill had looked down so low. Even if we had of, it is unlikely we would have realised the grey lump 500 metres in front of us was a cat. Garry said that he had become so familiar with the view over the previous week that he noticed a rock that wasn’t there the day before. I’ve really no idea how he did that but he earned a place in the mammalwatching hall of fame. And my first glimpse through the scope was of a large gray rock that – on closer inspection – had a long fluffy tail attached.

Snow Leopard, Panthera uncia

For the next 10 to 15 minutes we watched the animal stretch and then wander across the hillside before disappearing behind a ridge. Life doesn’t get much better.

Snow Leopard, Panthera uncia

Tomer’s video – taken with his superstrong 50x zoom – captures the moment well.

It was a distant sighting – just about visible to the naked eye – but so much the better because of that. Some of my favourite sightings have been distant: my first Grizzly Bear, first Rocky Mountain goat. There is something especially evocative about seeing such an animal from afar, framed by spectacular scenery, and completely oblivious to (or at least unperturbed by) our presence.

From left to right: Tomer, Smanla, me, Morten, Charles, Garry & Kate. (The other two in our group did not get up the hill in time to see the cat).

As we were busily high fiving each other and taking commemorative photos, Morten and I noticed stampeding blue sheep. And Morten spotted a second Leopard running in their direction. Only he saw it, and then only for a few seconds but the consensus was this must have been a second animal.

I rested during the afternoon and even had a chance to wash a few bits of my body beyond my hands and face before climbing back up the steep hill behind camp again for evening scanning. We couldn’t locate another cat. There was a bit of an anticlimactic atmosphere in camp during the afternoon. We were all delighted with the sighting but now what?

Saturday October 11: Rumbuk Camp

Each morning is successively colder than the last and overnight my water bottle – left next to my sleeping bag while I slept – was frozen solid when I woke up. Brrr. I heard a Stone Marten in the night again. So did Tomer, but his zeal for marten spotting was not enough to drag him out of a warm sleeping bag.

It was hard to motivate myself to climb the ridge behind camp for the pre-breakfast scan. One of the villagers had found fresh leopard tracks higher up the Rumbuk valley and so we spent a few hours looking and walking up the valley after breakfast.

Meanwhile the Europe’s Big 5 group went birding around Rumbuk village and saw a couple of Mountain Weasels, while magpie alarm calls put them onto a Stone Marten, apparently an unusual find in the day time even if one was visiting camp each night.

Most of our group were keen to stay at Rumbuk in search of more Snow Leopards. But Charles, Tomer and I were feeling a little stir crazy – or sick of staring at the same rocks day in day out – so we decided we would move on Sunday for a night or two to search for a Eurasian Lynx near Kandala Pass.

Sunday October 12 Rumbuk Camp to Yurutse Homestay

The tireless Smanla saw a Wolf at dawn before any of the tourists had joined him at the lookout. This is unusual at Rumbuk.

After breakfast Charles and I went into Rumbuk village to look for pikas. Smanla said pikas can be spotted “after the village” but we weren’t entirely sure where he meant and we didn’t see any

After lunch Charles, Tomer and I, together with our spotter, Damchos, and Phunchok (who’d arrived back from Leh) hiked up to the Yurutse Homestay in the late afternoon afternoon. We took a walkie-talkie with us and while we were en route got the message that a distant Snow Leopard had been spotted from camp. We were heading in its direction but didn’t see it.

Yurutse Homestay

The Yurutse Homestay was a warm and welcome luxury after camping. It was also like stepping back in time. We luxuriated in the heat from the stove and drank butter tea, which was just that: tea with butter and salt. I was not in a hurry to have a second cup.

Butter Tea

Phunchok cracked open a bottle of local rum that he’d bought with him to celebrate our Snow Leopard. It was one part alcohol to three parts rocket fuel. Before we could say “Eurasian Lynx” Tomer had sculled his very large shot. He was, he explained, unused to the idea of drinking with people who attempted to taste their alcohol. Charles and I quickly realised this was not alcohol we wanted to taste. And so it took us the best part of an hour to force a few drops of our shot down. We wondered whether Tomer would be alive in the morning.

Monday October 13: Yurutse Valley

Yurutse Homestay

Despite the absence of heating in my room, it was so warm in the night that I took my socks off for the first time since arriving in Leh.

We planned to spend the day looking for lynx and it was a pleasant hour’s hike up to the Kandala Pass basecamp, at the beginning of what we were told was the best lynx habitat in Hemis. It was a less pleasant – i.e. more steep – half an hour up to the second campsite where we had lunch.

We spent a couple of hours in each location looking for lynxes. It’s difficult to be sure how likely running into a lynx would be. My gut feeling is that the answer is ‘quite difficult, but easier than anywhere else I have been’. The lynxes like this section of the park. It’s up at between 4,000 – 47,00 metres and dotted with bushes. I suspect the bushes are a critical habitat requirement because they favour the lynxes ambush hunting and because they are home to lots of Woolly Hares, presumably a favourite prey.

On the way to lynx habitat

We didn’t find a lynx. However, we had only one spotter with us, the really excellent Damchos. If the entire Snow Leopard spotting machine had come up there with us I think there would be a really good chance of seeing an animal in a few days.

Woolly Hare, Lepus oiostolus

The other mammal spotting was excellent up there. We saw at least seven Woolly Hares, some of which were flushed by a Wolf, a bright yellow Wolf , in the morning. We saw the Wolf for a few minutes near the first campsite and then saw it – or another yellow Wolf – again in the afternoon just above the second, higher campsite. Though the animal was a few hundred metres away we watched it for at least 20 minutes as it tried to excavate a marmot from its burrow.

Wolf, Canis lupus. Picture by Tomer Ben-Yehuda.

We also saw several groups of Blue Sheep including a marvellous set of 21 males, and a couple of Mountain Weasels running around the campsite. This was the first day in Hemis that we’d seen four different species.

Long-tailed Marmots are common in this area too in the summer and apparently we had missed the last of them by only a few days. Mountain Voles are also apparently common near the vegetation along the valley bottom in the warmer months but we didn’t see any.

We spent the night at the homestay , wondering how best to spend our final two days in the park. Tomer and Charles had a close encouter with a mouse in their room.

Tuesday October 14: Yurutse Valley – Rumbuk Camp

I slept badly. Perhaps it was because we were a few hundred metres higher than we’d been before but I felt short of breath even while lying down. This is a classic problem related to altitude. In the morning we hiked back up to the upper campsite to spend a few more hours looking for a lynx but saw little in the way of mammals.

We had lunch at the homestay and headed back to camp at Rumbuk where we were happy to learn that all the rest of the group had had prolonged views of two Snow Leopards on Sunday evening. Although they were about 3 km away people had had a good scope view and had watched two animals for 90 minutes. We also heard that the Marten appeared 15 minutes after the rest of the camp had gone to bed the previous night. So Tomer resolved, yet again, to let nothing stand in his way between him and a Marten sighting.

After dinner a few of us stayed up to wait for the Stone Marten. I bailed at 10 p.m. and at 10.45 the marten returned to put on a show for Charles and Tomer.

Weds October 15: Rumbuk Camp

Our last full day in the park and we were by now all tired and ready to move on. I wandered back down the valley to look for pikas but saw only Large-eared Pika again at “Pika Point” (see the start of this report for details on this site).

Nubra Pika, Ochotona nubrica

In the evening Tomer spotted a pika, apparently a different species, very near camp. Charles and I went with him and got a long look at what was certainly a different species to the usual Large-eared flavour, a Nubra Pika (an ID later confirmed by an expert).

Nubra Pika, Ochotona nubrica

We spotted a Wolf from the campsite just before sunset and watched the animal move with impressive speed up the cliffs opposite us.

Wolf, Canis lupus

Dinner was festive and the chef put on his most impressive performance to date, serving both pizza and a Snow Leopard cake. We were sad to be leaving but extremely excited at the thought of tomorrow’s hot shower.

Snow Leopard cake

Thursday October 16: Rumbuk Camp to Leh

We woke to find a dusting of snow over the hills and our campsite. Quite beautiful though it evaporated as soon as the sunlight touched it.

One last look for me

After a last look for leopards we hiked the three hours back to Phunchok and the waiting cars. At 2 p.m. we were checking into the fancy Golden Dragon Hotel and at 2.05 p.m. I started a very very long shower. The rest of the day was spent shopping for souvenirs, checking email and enjoying a last dinner with the group, most of whom were about to head off for three nights to Tso Kar and some mammals of the Tibetan Plateau. I wished I was going.

Trip List

Large-eared Pika

Nubra Pika

House mouse

Woolly Hare

Ladakh Urial

Blue Sheep

Wolf

Red Fox

Mountain Weasel

Stone Marten

Snow Leopard

Stuff I Missed

I missed very little really that I was looking for other than lynx, which was always an outside chance and which would be easier to focus on in warmer months and when there was less attention to Snow Leopards. I do think there is a really good chance of seeing one in four or five days around the Kandala base camp. Mountain Voles and Long-tailed Marmots were both apparently hibernating and though I have seen them before I had an eye out for Royle’s Pika but did not see any that I was sure of. I assume they do occur somewhere in Hemis or Leh however.

Elsewhere in the park Siberian Ibex are occasionally present, while Argalis can usually be spotted around the top of Kandala Pass with some effort. I made no effort to see either species, both of which I had seen before and both of which are more easily seen elsewhere in Ladakh: the Ibex are easy to see around Ulley, while the Argalis are easier to see at Tso Kar.

Thank you

A big thanks to many people, including the other members of the group who remained cheerful despite the triple hardships of cold, altitude and absence of alcohol. But a special thanks to our guide Smanla, who is a phenomenally lovely and patient guy, with an enormous dedication to his work and the park and a great talent for spotting Snow Leopards.

Damchos, our spotter, was another Smanla in the making. He didn’t stop looking for animals once and, especially on our lynx trip, would stare through the scope for hours at a time, even when the rest of us had given up looking. And finally a big big thanks to Phunchok who organised a really first rate trip at a very affordable price and then went to great lengths to accommodate many last minute changes without any complaint. I recommend all three of them totally. So go to Ladakh and go now. Because mammal watching doesn’t get much better than seeing a Snow Leopard.

Smanla & co. Snow Leopard spotters extraordinaire.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.